C¶

C refuses to die and for good reason. Created in 1972, it still powers operating systems, embedded devices, network stacks, and critical infrastructure. Learn C and you'll understand how computers actually work.

Table of Contents¶

- 1. C Language Fundamentals

- 6. Numerical Operations: Arithmetic Operators

- 7. Relational & Logical Operations: Comparison Operators

- 8. Code Organization: Functions

- 2. Memory Management in C

- 3. Advanced C Programming

- 4. Secure Coding in C

- 23. Unix Security Model: File Permissions and User IDs

- 24. Common Vulnerabilities: Buffer Overflows

- 25. Input based Attacks: Format String Exploits

- 26. Integer Vulnerabilities: Overflows and Underflows

- 27. Time based Flaws: Race Conditions (TOCTOU)

- 28. Memory Corruption: Use After Free

- 29. Filesystem Security: Path Traversal

- 30. Defensive Programming: Secure Coding Patterns

- 31. Runtime Protections: Memory Safety Mitigations

- 5. Interfacing and Tooling

- 32. Network Programming: Socket I/O Basics

- 33. Database Interaction: SQL and Injection Prevention

- 34. Pattern Matching: Regular Expressions in C

- 35. Foreign Function Interface (FFI): Interfacing with Other Languages

- 36. Code Analysis: Static and Dynamic Analysis with GDB

- 37. Exploitation Lifecycle: From Triage to Mitigation Bypass

- 38. Building Securely: Hardening Compiler Flags

- 39. Preprocessor Directives

- 40. Bitwise Operators

- 41. Unions

- 42. Enums (Enumerations)

- 6. Advanced and Specialized Topics

- 43. Multithreading with Pthreads

- 44. Atomics and Memory Barriers

- 45. Signal Handling

- 46. Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

- 47. Memory mapped Files (mmap)

- 48. Advanced Data Structures: Linked Lists

- 49. The volatile Keyword

- 50. The const Keyword and its Nuances

- 51. Generic Programming with _Generic

- 52. setjmp and longjmp: Non local Jumps

- 53. Flexible Array Members

- 54. The goto Statement

- 55. Undefined Behavior, Sequence Points, and Strict Aliasing

- 56. Inline Functions and Linkage in Headers

- 57. Endianness and Byte Order

- 58. POSIX Low level I/O

- 59. errno and Error Handling

- 60. Randomness and Secure RNG

- 61. Floating Point Pitfalls and IEEE-754

- 62. Build Systems: Minimal Makefile

- 7. Security-Focused C Cookbook

- 63. Secure CLI Parsing with getopt/getopt_long

- 64. Safe String Handling Patterns

- 65. Secure Temporary Files with mkstemp

- 66. Privilege Dropping and Chroot

- 67. Constant time Comparisons

- 68. Password Hashing and Key Derivation

- 69. Logging with syslog

- 70. File Permissions and umask

- 71. Monotonic Time and Timeouts

- 8. Networking and Systems Cookbook

- 9. Project Structure and Build

- 10. Crypto and Security Primitives

- 11. OS Hardening and Sandboxing

- 12. Binary and Dynamic Linking Toolkit

- 13. Complete Basics Walkthrough

- 95. Getting Started: Compile and Run

- 96. Syntax and Comments

- 97. Output and Formatting Basics

- 98. Variables, Data Types, and Constants

- 99. Operators and Booleans

- 100. Control Flow: if/else and switch

- 101. Loops: while, for, break/continue

- 102. Arrays and Strings

- 103. User Input and Validation

- 104. Memory Addresses and Pointers

- 105. Functions, Parameters, Declarations

- 106. Recursion and Math Functions

- 14. Files and Structures Walkthrough

- 15. Errors and Debugging Walkthrough

- 16. Sockets Walkthrough

- 17. Common Headers Reference

- Appendix: Quick Reference

- Common GCC/Clang Flags

- Basic GDB Commands

- Valgrind Quickstart

- Sanitizers Quickstart

- pkg config Tips

- Static Analysis: clang tidy/cppcheck

- Fuzzing: AFL++/libFuzzer Quickstart

- Dangerous Functions to Avoid

- Useful Macros

- strace and ltrace Quickstart

- Profiling: perf and gprof

- Code Coverage: gcov and lcov

- Formatting: clang format

- EditorConfig

- Compilation Database and clangd

- Dockerized Builds

Part 1: C Language Fundamentals¶

1. Core Concepts of C¶

C was created by Dennis Ritchie at Bell Labs in the early 1970s to write Unix (yes, that Unix the operating system that Linux, macOS, and countless others are based on). It's a procedural language you write functions that do things step by step. Simple concept. Powerful execution.

What Makes C Different:

Manual Memory Management: Unlike Python, Java, or Go, C doesn't have garbage collection. You allocate memory explicitly with malloc() and free it with free(). This is terrifying for beginners but gives you complete control. Memory leaks? Your fault. Buffer overflows? Your fault. Use after free? Your fault. The compiler won't save you.

Compilation Model: C compiles directly to machine code. No virtual machine. No interpreted bytecode. What you write is what runs after the compiler translates it. This means: - Fast execution (no interpreter overhead) - Small binaries (no runtime included) - Platform specific (recompile for different architectures)

Pointer Power: C's most distinctive feature is pointers variables that hold memory addresses. They let you: - Pass large data structures efficiently (pass the address, not a copy) - Build complex data structures (linked lists, trees, graphs) - Interact with hardware directly - Create security vulnerabilities if you're not careful

The C Philosophy:

C trusts the programmer. It assumes you know what you're doing. It won't stop you from writing code that crashes. It won't prevent buffer overflows. It won't detect memory leaks. This freedom is powerful but dangerous especially in security sensitive code.

Key Characteristics: - low level Memory Access: Direct control via pointers power and responsibility in one feature - High Performance: Compiles to native machine code, no runtime overhead - Portability: Source code compiles on different platforms with minimal changes (but beware platform specific quirks) - Modularity: Functions and libraries keep code organized and reusable

// Here's a basic "Hello, World!" in C

#include <stdio.h> // This brings in the standard I/O stuff

int main() {

// Every C program starts here

printf("Hello, World!\n"); // This prints to the screen

return 0; // Zero means everything went okay

}

2. Conditional Logic: if, else if, else¶

Conditional statements control the flow of a program based on whether a condition is true or false.

if: Executes a block of code if a condition is true.else if: Checks another condition if the previousiforelse ifwas false.else: Executes a block of code if all preceding conditions are false.

#include <stdio.h>

void check_number(int num) {

if (num > 0) {

printf("%d is positive.\n", num);

} else if (num < 0) {

printf("%d is negative.\n", num);

} else {

printf("%d is zero.\n", num);

}

}

int main() {

check_number(10);

check_number(-5);

check_number(0);

return 0;

}

3. Looping with while and do while¶

Loops are used to execute a block of code repeatedly.

whileloop: Executes as long as a condition is true. The condition is checked before each iteration.do whileloop: Similar towhile, but the condition is checked after each iteration, guaranteeing at least one execution.

#include <stdio.h>

void while_loop_example() {

int i = 0;

printf("While loop:\n");

while (i < 5) {

printf("i = %d\n", i);

i++; // Increment i

}

}

void do_while_loop_example() {

int i = 0;

printf("\nDo while loop:\n");

do {

printf("i = %d\n", i);

i++;

} while (i < 5);

}

int main() {

while_loop_example();

do_while_loop_example();

return 0;

}

4. Structured Looping: The for Loop¶

The for loop is ideal for when the number of iterations is known beforehand. It combines initialization, condition, and increment/decrement into a single line.

#include <stdio.h>

void for_loop_example() {

printf("For loop:\n");

// (initialization; condition; update)

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

printf("i = %d\n", i);

}

}

int main() {

for_loop_example();

return 0;

}

5. Data Storage: Variables and Data Types¶

Variables are named storage locations. Every variable in C has a data type, which determines the size and layout of the variable's memory.

Common Data Types: - int: Integers (e.g., 10, -5, 0). - float: Single precision floating point numbers (e.g., 3.14). - double: Double precision floating point numbers. - char: A single character (e.g., 'a', 'Z'). - _Bool: Boolean values (true or false). Requires #include <stdbool.h>.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdbool.h> // For bool type

int main() {

int age = 30;

float pi = 3.14159f; // 'f' suffix for float literals

double gravity = 9.80665;

char initial = 'J';

bool is_active = true;

printf("Age: %d\n", age);

printf("Pi: %f\n", pi);

printf("Gravity: %lf\n", gravity); // %lf for double

printf("Initial: %c\n", initial);

printf("Is Active: %d\n", is_active); // Booleans are printed as 0 or 1

return 0;

}

5b. Data types: sizes, ranges, buffers, and special cases¶

- The C standard defines minimum ranges, not exact sizes. Use sizeof(type), limits.h, float.h, and stdint.h types for portability.

- Common data models and implications: ILP32 (32-bit): int=32, long=32, pointer=32 LP64 (Linux/macOS 64-bit): int=32, long=64, pointer=64 LLP64 (Windows 64-bit): int=32, long=32, long long=64, pointer=64

- Typical sizes (do not hardcode; measure with sizeof): char: 1 byte, CHAR_BIT is usually 8. Signedness of char is implementation defined; prefer signed char/unsigned char explicitly. _Bool/bool: 1 byte when included via

; prints as 0/1 with %d. short: ≥16-bit int: ≥16-bit (commonly 32-bit) long: 32-bit on LLP64; 64-bit on LP64 long long: ≥64-bit (commonly 64-bit) float: typically 32-bit IEEE-754 double: 64-bit long double: 80-bit extended on some ABIs, 64-bit on others. size_t/ptrdiff_t: unsigned/signed types for sizes and pointer differences; width matches pointer width. wchar_t: 2 bytes on Windows (UTF-16 code unit), 4 bytes on Linux (UTF-32 code unit). For UTF-16/32 in C11, see (char16_t/char32_t). Pointers: 4 bytes on 32-bit, 8 bytes on 64-bit; function pointers may differ from object pointers, do not cast between them portably. - Enums: underlying type is an integer type large enough to hold enumerators; not necessarily int; size is implementation defined.

- Alignment and padding: struct layout may include padding. Use _Alignof(T) (C11) to query alignment. Avoid packed layouts unless interfacing with wire formats.

- Endianness: varies by platform (x86 is little endian). Convert at I/O boundaries using htons/ntohs, htonl/ntohl, etc.

Buffers, strings, and byte counts¶

- C strings are NUL-terminated; always account for the terminator. Example: char s[6] = "hello"; // 5+1

- Use sizeof(array) to get total bytes of an array in the same scope; number of elements is sizeof(array)/sizeof(array[0]). Arrays decay to pointers when passed to functions.

- Prefer snprintf, strnlen, and explicit length tracking for safety. Be wary: strncpy does not guarantee NUL-termination if truncated.

- For memory copying, memcpy requires non overlapping regions; use memmove for overlaps.

- For binary I/O, compute sizes as element_count * sizeof(T) and use size_t for counts.

Print sizes at runtime

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <limits.h>

#include <float.h>

int main(void){

printf("CHAR_BIT=%d\n", CHAR_BIT);

printf("sizeof(void*)=%zu sizeof(long)=%zu sizeof(long long)=%zu\n",

sizeof(void*), sizeof(long), sizeof(long long));

printf("sizeof(float)=%zu sizeof(double)=%zu sizeof(long double)=%zu\n",

sizeof(float), sizeof(double), sizeof(long double)); // ==> And repeat with needed datatype if you get what i mean ^_^

return 0;

}

Guidance

- When size matters, use fixed width types from

(e.g., uint32_t, int64_t). - Prefer unsigned char for raw bytes, not char.

- For Unicode, prefer libraries; wchar_t width varies.

provides char16_t/char32_t types. - If you need anything further than that just google it or ask chatgpt | => (

GOOGLE IS YOUR FRIEND!)

6. Numerical Operations: Arithmetic Operators¶

C supports standard arithmetic operators for numerical calculations.

+(addition),-(subtraction),*(multiplication),/(division)%(modulus): Returns the remainder of a division.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int a = 10;

int b = 3;

printf("a + b = %d\n", a + b);

printf("a b = %d\n", a b);

printf("a * b = %d\n", a * b);

printf("a / b = %d\n", a / b); // Integer division truncates the result

printf("a %% b = %d\n", a % b); // Modulus

return 0;

}

7. Relational & Logical Operations: Comparison Operators¶

These operators are used to compare values and create complex conditions.

Relational Operators: - == (equal to), != (not equal to) - > (greater than), < (less than) - >= (greater than or equal to), <= (less than or equal to)

Logical Operators: - && (AND): True if both operands are true. - || (OR): True if at least one operand is true. - ! (NOT): Inverts the truth value of its operand.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

int main() {

int x = 5;

int y = 10;

printf("x == 5: %d\n", x == 5); // True (1)

printf("x != y: %d\n", x != y); // True (1)

printf("x > y: %d\n", x > y); // False (0)

bool a = true;

bool b = false;

printf("a && b: %d\n", a && b); // False (0)

printf("a || b: %d\n", a || b); // True (1)

printf("!a: %d\n", !a); // False (0)

return 0;

}

8. Code Organization: Functions¶

Functions are self contained blocks of code that perform a specific task. They improve code reusability and organization.

- Declaration (Prototype): Tells the compiler about a function's name, return type, and parameters.

- Definition: Provides the actual body of the function.

#include <stdio.h>

// Function declaration (prototype)

int add(int a, int b);

int main() {

int result = add(5, 3); // Function call

printf("The sum is: %d\n", result);

return 0;

}

// Function definition

int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b; // Return statement

}

9. Working with Collections: Arrays¶

Arrays store a fixed size sequential collection of elements of the same type.

- Elements are accessed using a zero based index.

- The name of the array often acts as a pointer to the first element.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Declare and initialize an array of 5 integers

int numbers[5] = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

// Access and print the third element (index 2)

printf("The third element is: %d\n", numbers[2]); // Output: 30

// Modify an element

numbers[0] = 5;

// Iterate through the array

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

printf("Element at index %d: %d\n", i, numbers[i]);

}

return 0;

}

10. Understanding Pointers¶

A pointer is a variable that stores the memory address of another variable. They are fundamental to C for tasks like dynamic memory allocation and efficient data manipulation.

&(address of operator): Gets the memory address of a variable.*(dereference operator): Accesses the value at a memory address stored in a pointer.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int var = 20; // An integer variable

int *ptr; // A pointer to an integer

ptr = &var; // Store the address of 'var' in 'ptr'

printf("Value of var: %d\n", var);

printf("Address of var: %p\n", (void *)&var); // Use %p for pointers

printf("Value of ptr: %p\n", (void *)ptr);

printf("Value pointed to by ptr: %d\n", *ptr); // Dereference the pointer

*ptr = 30; // Modify the value at the address stored in ptr

printf("New value of var: %d\n", var); // var is now 30

return 0;

}

Part 2: Memory Management in C¶

10b. Pointer deep dive¶

- Qualifiers and meaning: Pointer to const vs const pointer: const int* p (cannot modify p, can reseat p); int const p (can modify p, cannot reseat p); const int const p (neither). volatile affects optimization of accesses; use for MMIO/signal handlers, not as a threading primitive. restrict (C99): promises no other pointer aliases the same object for the lifetime of the pointer; enables vectorization. Only apply when you can guarantee it.

- Arrays and pointer decay: In most expressions, arrays decay to pointers to their first element (int a[10]; a -> &a[0]). sizeof(a) yields total bytes; sizeof(a+0) yields pointer size. &a has type int ()[10] (pointer to array) which is different from int (pointer to element). Function parameters declared as int a[] or int a[10] are equivalent to int* a; the length is not preserved. Pass lengths explicitly.

- Pointers to pointers and 2D arrays: int p is not the same as int a[M][N]. Use int (*pa)[N] for a pointer to an array of N ints when passing 2D arrays: void f(int (*pa)[N]){...}. Memory layout differs: a true 2D array is contiguous; an int typically points to an array of pointers.

- Pointer arithmetic and bounds: Adding/subtracting advances by element size: p+1 moves sizeof(*p) bytes. Subtracting two pointers to elements of the same array yields ptrdiff_t count of elements. You may form a pointer one past the end of an array, but you must not dereference it. Forming pointers outside [begin, end+1] is undefined.

- Alignment and aliasing: Many architectures require aligned accesses; misaligned dereference can trap or be slow. Use _Alignof(T) and ensure proper alignment of buffers. Strict aliasing: accessing an object via an incompatible pointer type is undefined behavior. Exceptions: char/unsigned char/signed char may alias any object. Use memcpy for type punning.

- Bytes and character types: Use unsigned char* for raw binary data. The three character types (char, signed char, unsigned char) are distinct types.

- Function pointers: Object and function pointers may have different representations; do not cast between them portably. Always call through the correct prototype.

- Comparisons and ordering: Equality/inequality comparisons are defined for pointers to the same object or NULL; ordering comparisons (<, >, etc.) are only defined within the same array object.

- Lifetime pitfalls: Do not return the address of a local (stack) variable. Clear or set to NULL after free to avoid dangling pointers.

Examples

Array vs pointer and sizeof:¶

#include <stdio.h>

void takes_ptr(int *p){ (void)p; }

void takes_arr(int a[], size_t n){ (void)a; (void)n; }

int main(void){

int a[5] = {0};

printf("sizeof(a)=%zu elements=%zu\n", sizeof a, sizeof a/sizeof a[0]);

int *p = a; // decay

printf("sizeof(p)=%zu\n", sizeof p);

takes_ptr(a); // decays to int*

takes_arr(a, sizeof a/sizeof a[0]);

}

Discussion: - sizeof(a) yields total bytes of the array within the same scope; once it decays to a pointer (int*), sizeof gives the pointer size. - Function parameters declared as int a[] or int a[10] are equivalent to int* a; array length is not preserved and must be passed explicitly. - Prefer a helper to compute element count at the call site: ARRAY_LEN(a) (defined in Appendix). - sizeof on pointers reflects ABI width (4 bytes on 32-bit, 8 bytes on 64-bit), not the number of elements.

Pointer to array-(2D):¶

#include <stdio.h>

void row_sum(size_t rows, size_t cols, int (*m)[cols]){

for (size_t r=0; r<rows; r++){

long s=0; for(size_t c=0;c<cols;c++) s += m[r][c];

printf("row %zu sum=%ld\n", r, s);

}

}

int main(void){

int m[2][3] = {{1,2,3},{4,5,6}};

row_sum(2,3,m);

}

Discussion: - The parameter int (m)[cols] is a “pointer to an array of cols int”, preserving the row length so m[r][c] indexes correctly. - This matches a true 2D array stored contiguously. In contrast, int* often refers to a jagged structure (array of pointers). - When cols is not a compile time constant, using a VLA parameter (int (*m)[cols]) is a C99 feature; ensure your compiler flags enable it.

restrict example:¶

#include <stddef.h>

void saxpy(size_t n, float a, const float * restrict x, float * restrict y){

for (size_t i=0;i<n;i++) y[i] = a*x[i] + y[i];

}

Discussion: - restrict asserts that, for the lifetime of the pointer, no other pointer aliases the same array. Compilers can vectorize/hoist loads based on this. - Violating restrict causes undefined behavior and may silently yield wrong results under optimization. - Combine with const for read only inputs: const float* restrict x, which communicates both immutability and non aliasing.

11. Processor Fundamentals: x86 Architecture Basics¶

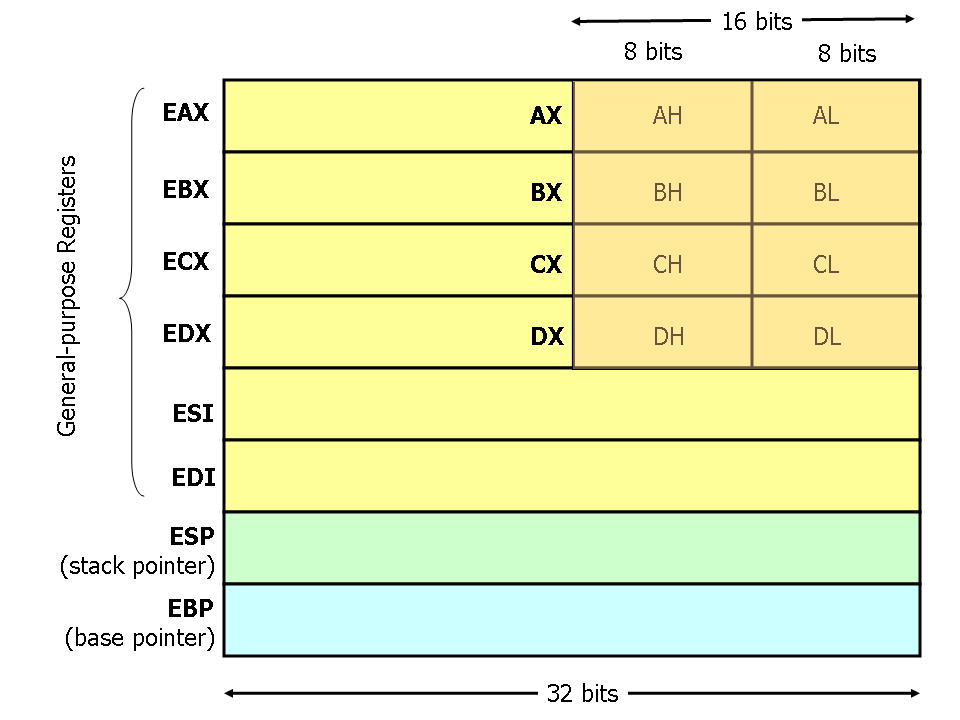

Understanding the underlying processor architecture is crucial for low level programming. The x86 architecture has several key components:

- Registers: Small, fast storage locations within the CPU. General purpose registers (like

EAX,EBX,ECX,EDXin 32-bit) are used for arithmetic and data movement. - Stack: A region of memory used for local variables and function calls. It operates on a Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) basis.

- Calling Conventions: Rules that govern how functions pass arguments and return values (e.g.,

cdecl,stdcall).

12. Integer Representation: Signed vs. Unsigned¶

Integers can be signed (positive, negative, or zero) or unsigned (only positive or zero).

- Signed Integers: Use one bit (the most significant bit) to represent the sign. A common representation is two's complement.

- Unsigned Integers: Use all bits to represent the magnitude, allowing for a larger range of positive values.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

signed int signed_val = -1; // Can be negative

unsigned int unsigned_val = 4294967295; // Max value for a 32-bit unsigned int

printf("Signed value: %d\n", signed_val);

printf("Unsigned value: %u\n", unsigned_val); // Use %u for unsigned

// Overflow behavior

unsigned int max_unsigned = 4294967295;

max_unsigned = max_unsigned + 1; // Wraps around to 0

printf("Overflowed unsigned: %u\n", max_unsigned);

return 0;

}

13. Advanced Pointers: Pointer Arithmetic and void Pointers¶

- Pointer Arithmetic: You can perform arithmetic operations on pointers. Incrementing a pointer moves it to the next element of its type, not just the next byte.

voidPointers: A generic pointer that can point to any data type. It must be cast to a specific type before being dereferenced.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int numbers[] = {10, 20, 30, 40};

int *ptr = numbers; // ptr points to numbers[0]

// Pointer arithmetic

printf("Value at ptr: %d\n", *ptr);

ptr++; // Move to the next integer

printf("Value at ptr after increment: %d\n", *ptr); // Now points to 20

// Void pointer

void *void_ptr;

int x = 100;

void_ptr = &x;

// Cannot dereference void_ptr directly: *void_ptr is illegal

// Must cast it first

printf("Value via void pointer: %d\n", *(int *)void_ptr);

return 0;

}

14. Memory Layout: Segments¶

A C program's memory is divided into several segments:

- Text: Contains the compiled machine code. Usually read only.

- Data: Stores initialized global and static variables.

- BSS (Block Started by Symbol): Stores uninitialized global and static variables. The system initializes them to zero.

- Heap: For dynamic memory allocation (

malloc,free). Grows upwards. - Stack: For local variables, function parameters, and return addresses. Grows downwards.

15. Dynamic Memory: malloc, free, and The Heap¶

The heap is used for allocating memory at runtime when the size is not known at compile time.

malloc(size): Allocates a block of memory ofsizebytes. Returns avoidpointer to the allocated space, orNULLif the request fails.free(ptr): Deallocates a previously allocated block of memory.

Rule of Thumb: For every malloc, there must be a corresponding free. Failure to free memory leads to memory leaks.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h> // For malloc and free

int main() {

int *arr;

int n = 5;

// Allocate memory for 5 integers on the heap

arr = (int *)malloc(n * sizeof(int));

// Check if allocation was successful

if (arr == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "Memory allocation failed\n");

return 1;

}

// Use the allocated memory

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

arr[i] = i + 1;

}

printf("Dynamically allocated array:\n");

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

printf("%d ", arr[i]);

}

printf("\n");

// Free the allocated memory

free(arr);

arr = NULL; // Good practice to set pointer to NULL after freeing

return 0;

}

16. Data Structures: structs and Memory Alignment¶

struct allows you to group variables of different data types under a single name.

- Memory Alignment: Compilers often add padding between struct members to ensure they are aligned on memory addresses that are multiples of their size. This can improve performance but increases the struct's overall size.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stddef.h> // For offsetof

// Define a struct

struct Student {

char initial;

int student_id;

float gpa;

};

// The __attribute__((packed)) tells the compiler not to add padding.

// This can save space but may lead to slower access on some architectures.

struct PackedStudent {

char initial;

int student_id;

float gpa;

} __attribute__((packed));

int main() {

struct Student s1;

s1.initial = 'A';

s1.student_id = 12345;

s1.gpa = 3.8f;

printf("Student ID: %d\n", s1.student_id);

// Demonstrate padding and alignment

printf("Size of Student struct: %zu bytes\n", sizeof(struct Student));

printf("Size of PackedStudent struct: %zu bytes\n", sizeof(struct PackedStudent));

printf("Offset of student_id in Student: %zu\n", offsetof(struct Student, student_id));

printf("Offset of student_id in PackedStudent: %zu\n", offsetof(struct PackedStudent, student_id));

return 0;

}

Part 3: Advanced C Programming¶

17. Input and Output: command line Arguments¶

C programs can receive arguments from the command line through the main function.

int argc: The number of command line arguments (argument count).char *argv[]: An array of strings (character pointers) representing the arguments (argument vector).argv[0]is always the name of the program itself.

#include <stdio.h>

// Run as: ./myprogram arg1 arg2

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("Program name: %s\n", argv[0]);

printf("Number of arguments: %d\n", argc);

if (argc > 1) {

printf("Arguments provided:\n");

for (int i = 1; i < argc; i++) {

printf(" argv[%d]: %s\n", i, argv[i]);

}

} else {

printf("No additional arguments were provided.\n");

}

return 0;

}

18. Variable Lifetime: Scope and Storage Classes¶

- Scope: The region of the program where a variable is accessible. Local Scope: Declared inside a function or block. Global Scope: Declared outside all functions.

- Storage Classes: Determine a variable's lifetime and visibility.

auto: The default for local variables.static: A local static variable persists between function calls. A global static variable is visible only within the file it's declared in.extern: Declares a variable that is defined in another file.register: Suggests to the compiler that a variable should be stored in a CPU register for faster access.

#include <stdio.h>

int global_var = 10; // Global variable

void counter() {

static int count = 0; // Static local variable

count++;

printf("This function has been called %d time(s).\n", count);

}

int main() {

counter();

counter();

counter();

return 0;

}

19. Type Safety: Typecasting and Conversions¶

Typecasting is a way to convert a variable from one data type to another.

- Implicit Conversion: The compiler automatically converts types (e.g.,

inttofloatin an expression). - Explicit Conversion (Casting): Manually done by the programmer using

(type_name)expression.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int a = 10;

int b = 3;

float result;

// Without casting, integer division occurs

result = a / b;

printf("Result without casting: %f\n", result); // Output: 3.000000

// With explicit casting to float

result = (float)a / b;

printf("Result with casting: %f\n", result); // Output: 3.333333

return 0;

}

20. Function Pointers and Callbacks¶

A function pointer stores the address of a function. This allows functions to be passed as arguments to other functions, a technique known as a callback.

#include <stdio.h>

void say_hello() {

printf("Hello!\n");

}

void say_goodbye() {

printf("Goodbye!\n");

}

// This function takes a function pointer as an argument

void execute_greeting(void (*greeting_func)()) {

printf("Executing a greeting:\n");

greeting_func(); // Call the function via the pointer

}

int main() {

// Declare a function pointer

void (*func_ptr)();

// Assign it to a function

func_ptr = say_hello;

func_ptr(); // Call the function

// Use callbacks

execute_greeting(say_hello);

execute_greeting(say_goodbye);

return 0;

}

21. File Handling: I/O Operations¶

C provides a set of functions in <stdio.h> for file input and output.

FILE *fopen(const char *filename, const char *mode): Opens a file. Modes include"r"(read),"w"(write),"a"(append).int fclose(FILE *stream): Closes a file.fprintf(FILE *stream, ...): Writes formatted output to a file.fscanf(FILE *stream, ...): Reads formatted input from a file.fgets(char *str, int n, FILE *stream): Reads a line from a file.fputs(const char *str, FILE *stream): Writes a string to a file.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

FILE *file_ptr;

char buffer[256];

// Write to a file

file_ptr = fopen("example.txt", "w");

if (file_ptr == NULL) {

perror("Error opening file for writing");

return 1;

}

fprintf(file_ptr, "This is a test file.\n");

fprintf(file_ptr, "C file I/O is powerful.\n");

fclose(file_ptr);

// Read from the file

file_ptr = fopen("example.txt", "r");

if (file_ptr == NULL) {

perror("Error opening file for reading");

return 1;

}

printf("Contents of example.txt:\n");

while (fgets(buffer, sizeof(buffer), file_ptr) != NULL) {

printf("%s", buffer);

}

fclose(file_ptr);

return 0;

}

22. String Manipulation and printf Formatting¶

In C, a string is an array of characters terminated by a null character (\0).

- Format Specifiers for

printf:%dor%i: Signed integer%u: Unsigned integer%f: Floating point number%c: Character%s: String%p: Pointer address%x: Hexadecimal number

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h> // For string functions

int main() {

char str1[20] = "Hello";

char str2[] = "World";

char buffer[40];

// Concatenate strings

strcpy(buffer, str1); // Copy str1 to buffer

strcat(buffer, " "); // Append a space

strcat(buffer, str2); // Append str2

printf("Concatenated string: %s\n", buffer);

printf("Length of buffer: %zu\n", strlen(buffer));

// Formatted printing

printf("Number: %04d\n", 42); // Padded with leading zeros

printf("Hex: %%#x\n",-255); // With 0x prefix

printf("Float: %.2f\n", 3.14159);

return 0;

}

22b. String handling deep dive¶

- Safe input Prefer fgets; strip trailing newline. Avoid gets; for scanf/sscanf, always use field widths (e.g., "%31s").

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

size_t safe_getline(char *buf, size_t sz, FILE *in){

if (!fgets(buf, sz, in)) return 0;

size_t n = strcspn(buf, "\n");

if (n < sz && buf[n] == '\n') buf[n] = '\0';

return n;

}

Discussion: - fgets stops at newline or when the buffer fills; strcspn finds the newline to replace it with a NUL terminator. - Return value is the length excluding the newline; on EOF/error, returns 0 (differentiate with feof/ferror as needed). - Always pass the full buffer size to fgets; it reserves space for the terminator.

- Robust numeric parsing: strtol/strtoul/strtod with error checks.

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <limits.h>

int parse_int(const char *s, int *out){

errno = 0; char *end; long v = strtol(s, &end, 10);

if (errno || end == s || *end != '\0' || v < INT_MIN || v > INT_MAX) return -1;

*out = (int)v; return 0;

}

Discussion: - strtol sets errno and produces an end pointer; check both to detect invalid input or garbage suffixes. - Cast to int only after verifying the long falls within [INT_MIN, INT_MAX]. - For hex/auto base parsing, use base=0 so prefixes like 0x are handled, but still validate end pointer.

- Bounded formatting and concatenation: use snprintf and check truncation.

#include <stdio.h>

int join3(const char *a, const char *b, const char *c, char *out, size_t outsz){

int n = snprintf(out, outsz, "%s%s%s", a, b, c);

return (n < 0 || (size_t)n >= outsz) ? -1 : 0;

}

Discussion: - snprintf returns the number of chars that would have been written (excluding the terminator); compare against outsz to detect truncation. - Prefer assembling into a single call or a scratch buffer rather than chained strcat to avoid quadratic scans and overflow risk. - For dynamic sizes, pair snprintf with a capacity managed buffer (see append_str helper).

- Tokenization: strtok_r for re entrant; consider strsep when empty fields matter.

#include <string.h>

size_t split_csv(char *s, char *tok[], size_t max){

size_t n = 0; char *save = NULL; char *p = strtok_r(s, ",", &save);

while (p && n < max) { tok[n++] = p; p = strtok_r(NULL, ",", &save); }

return n;

}

Discussion: - strtok_r modifies the input by inserting NULs; duplicate the string first if you must keep the original intact. - It collapses consecutive delimiters; if you need empty fields, consider strsep (BSD/GNU). - tok holds pointers into s; do not free tokens individually.

- Dynamic string building with realloc growth.

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

int append_str(char **dst, size_t *len, size_t *cap, const char *src){

size_t sl = strlen(src), need = *len + sl + 1;

if (need > *cap){ size_t nc = (*cap? *cap*2 : 64); while (nc < need) nc *= 2;

char *p = realloc(*dst, nc); if (!p) return -1; *dst = p; *cap = nc; }

memcpy(*dst + *len, src, sl+1); *len += sl; return 0;

}

Discussion: - The exponential growth strategy amortizes reallocation; track both current length and capacity. - Copy sl+1 bytes to include the NUL terminator so the destination stays a valid C string. - On realloc failure, the original pointer remains valid; propagate -1 to allow the caller to handle OOM.

-

Encodings/locales char* is bytes, not Unicode. Use iconv/ICU for conversions. mbstowcs/wcsrtombs depend on current locale (setlocale). Do not assume wchar_t width (2 on Windows, 4 on Linux).

-

Zeroization helper

void secure_bzero(void *p, size_t n){ volatile unsigned char *q = p; while (n--) *q++ = 0; }

Discussion: - secure_bzero uses a volatile qualified pointer to inhibit dead store elimination; many platforms provide explicit_bzero or memset_s for this purpose. - Register resident or temporary secrets cannot be reliably zeroized; minimize lifetime and use dedicated APIs for sensitive material. - Zeroization complements but does not replace proper key management, privilege separation, and process isolation.

Part 4: Secure Coding in C¶

23. Unix Security Model: File Permissions and User IDs¶

- File Permissions: Control who can read, write, or execute a file. Permissions are set for the owner, the group, and others.

- User IDs (UID) and Group IDs (GID): Identify users and groups.

setuid: A special permission that allows an executable to run with the privileges of the file's owner, not the user who executed it. This is powerful but dangerous if the program is vulnerable.

24. Common Vulnerabilities: Buffer Overflows¶

A buffer overflow occurs when a program writes data beyond the boundary of a buffer. This can corrupt data, crash the program, or be exploited to execute arbitrary code.

- Stack Overflow: Occurs when a buffer on the stack is overflowed.

- Heap Overflow: Occurs when a dynamically allocated buffer on the heap is overflowed.

Vulnerable Code Example:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void vulnerable_function(char *input) {

char buffer[10];

// strcpy does not check buffer boundaries, leading to a potential overflow

strcpy(buffer, input);

printf("You entered: %s\n", buffer);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

if (argc > 1) {

vulnerable_function(argv[1]);

}

return 0;

}

strncpy or snprintf which limit the number of bytes written. // A safer way to copy a string

strncpy(buffer, input, sizeof(buffer) 1);

buffer[sizeof(buffer) 1] = '\0'; // Ensure null termination

25. Input based Attacks: Format String Exploits¶

A format string vulnerability occurs when user supplied input is used as the format string in functions like printf. Attackers can use format specifiers like %x to read from the stack or %n to write to arbitrary memory locations.

Vulnerable Code:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

if (argc > 1) {

// Vulnerable: The user's input is passed directly as the format string

printf(argv[1]);

}

return 0;

}

// Safe: Always use a static format string

printf("%s", argv[1]);

26. Integer Vulnerabilities: Overflows and Underflows¶

An integer overflow occurs when an arithmetic operation results in a value that is too large to be stored in the variable's data type. This can lead to unexpected behavior and security flaws, especially in calculations involving memory allocation or buffer sizes.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <limits.h> // For INT_MAX

int main() {

int x = INT_MAX; // The maximum value for a signed int

printf("INT_MAX = %d\n", x);

x = x + 1; // This will overflow

printf("INT_MAX + 1 = %d\n", x); // Wraps around to a large negative number

return 0;

}

27. Time based Flaws: Race Conditions-(TOCTOU)¶

TOCTOU stands for "Time of-Check to Time of-Use." It's a race condition where a program checks for a condition (e.g., a file's permissions) and then performs an action based on that check. An attacker can change the state between the check and the use to gain an advantage.

Conceptual Example: 1. Check: Program checks if file.txt is owned by the user. 2. Attacker Action: Attacker quickly replaces file.txt with a symbolic link to /etc/shadow. 3. Use: Program proceeds to write to file.txt, but is now writing to the system's password file.

28. Memory Corruption: Use After Free¶

A use after free vulnerability occurs when a program continues to use a pointer after the memory it points to has been deallocated (free'd). This can lead to crashes or arbitrary code execution if an attacker can control the contents of the reallocated memory.

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int *ptr = (int *)malloc(sizeof(int));

*ptr = 100;

printf("Value before free: %d\n", *ptr);

free(ptr); // Deallocate the memory

// VULNERABILITY: ptr is now a "dangling pointer"

// Accessing it is undefined behavior.

printf("Value after free: %d\n", *ptr); // This might crash or print garbage

// An attacker could try to allocate new memory that happens to be at the same

// address, and then this program would be reading the attacker's data.

return 0;

}

NULL immediately after freeing them. 29. Filesystem Security: Path Traversal¶

A path traversal (or directory traversal) attack allows an attacker to access files and directories outside the intended directory. This happens when the program uses user supplied input to construct a file path without proper validation.

Vulnerable Code:

// User provides input like "../../../etc/passwd"

char path[100] = "/var/www/html/";

strcat(path, user_input); // Attacker can now read any file on the system

FILE *fp = fopen(path, "r");

.., /, and other special characters, or use a known good allowlist of characters. 30. Defensive Programming: Secure Coding Patterns¶

- Input Validation: Never trust user input. Validate its length, type, format, and range.

- Principle of Least Privilege: Run processes with the minimum permissions necessary.

- Use Safe APIs: Prefer functions like

snprintfandstrncpyover their unsafe counterparts (sprintf,strcpy). - Error Handling: Check the return values of all functions, especially those involving memory allocation or I/O.

31. Runtime Protections: Memory Safety Mitigations¶

Modern operating systems and compilers provide several protections against memory corruption attacks:

- ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization): Randomizes the memory locations of the stack, heap, and libraries, making it harder for attackers to predict target addresses.

- DEP/NX (Data Execution Prevention / No eXecute): Marks memory regions like the stack and heap as non executable, preventing attackers from injecting and running shellcode directly from them.

- Stack Canaries: A secret value placed on the stack before a function's local variables. If a buffer overflow overwrites the canary, the program can detect the corruption and terminate before a vulnerable return address is used.

Part 5: Interfacing and Tooling¶

32. Network Programming: Socket I/O Basics¶

Sockets provide a standard way for programs to communicate over a network.

Basic TCP Client Workflow: 1. socket(): Create a socket. 2. connect(): Connect to a server. 3. send() / recv() (or write() / read()): Exchange data. 4. close(): Close the connection.

33. Database Interaction: SQL and Injection Prevention¶

When interacting with SQL databases, it's critical to prevent SQL injection. This occurs when user input is concatenated directly into an SQL query, allowing an attacker to alter the query's logic.

Vulnerable Query:

char query[200];

sprintf(query, "SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '%s'", user_input);

34. Pattern Matching: Regular Expressions in C¶

While C does not have built in regex support, you can use libraries like PCRE (Perl Compatible Regular Expressions).

Common Pitfalls: - ReDoS (Regular Expression Denial of Service): Poorly written expressions can have exponential execution time on certain inputs, allowing an attacker to freeze the program. - Anchors: Use ^ and $ to anchor matches to the beginning and end of a string to avoid partial matches.

35. Foreign Function Interface-(FFI): Interfacing with Other Languages¶

FFI allows code written in one language to call functions in another. C is often the "lingua franca" for this because most languages can interface with C. This involves matching data types and calling conventions.

36. Code Analysis: Static and Dynamic Analysis with GDB¶

- Static Analysis: Analyzing code without executing it. Tools like

cppcheck,clang analyzer, and commercial static analysis security testing (SAST) tools can find potential bugs and vulnerabilities. - Dynamic Analysis: Analyzing code while it is running. GDB (GNU Debugger): An essential tool for debugging C programs. You can set breakpoints, inspect variables, examine memory, and step through code execution. Sanitizers: Compiler features like AddressSanitizer (ASan) and UndefinedBehaviorSanitizer (UBSan) detect memory errors and undefined behavior at runtime.

37. Exploitation Lifecycle: From Triage to Mitigation Bypass¶

Developing an exploit for a C program often follows these steps: 1. Triage: Confirm the crash and determine if it's exploitable. 2. Control EIP/RIP: Craft an input that allows you to control the instruction pointer (the return address). 3. Find Space for Shellcode: Find a location in memory to place your malicious code. 4. Bypass Mitigations: Develop techniques to defeat ASLR, DEP, and canaries (e.g., Return-Oriented Programming ROP).

38. Building Securely: Hardening Compiler Flags¶

When compiling C code, use flags to enable security features:

gcc -fstack protector all: Enable stack canaries.gcc -Wl,-z,relro,-z,now: Enable RELRO (Relocation read only) to make parts of the binary read only after loading.gcc -pie -fPIE: Create a Position-Independent Executable, necessary for ASLR.gcc -D_FORTIFY_SOURCE=2: Adds checks to functions likememcpyandprintfto prevent some overflows.

39. Preprocessor Directives¶

The C preprocessor modifies the source code before compilation. - #include: Includes a header file. - #define: Defines a macro or a constant. - #ifdef, #ifndef, #if, #else, #elif, #endif: Conditional compilation. - #pragma: Issues special commands to the compiler.

#include <stdio.h>

#define PI 3.14159

#define-SQUARE(x) ((x) * (x))

int main() {

printf("Pi is approximately: %f\n", PI);

printf("Square of 5 is: %d\n", SQUARE(5));

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("Debug mode is ON.\n");

#else

printf("Debug mode is OFF.\n");

#endif

return 0;

}

40. Bitwise Operators¶

Bitwise operators perform operations on individual bits of integer types. - & (Bitwise AND) - | (Bitwise OR) - ^ (Bitwise XOR) - ~ (Bitwise NOT) - << (Left Shift) - >> (Right Shift)

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

unsigned char a = 5; // 00000101

unsigned char b = 3; // 00000011

printf("a & b = %d\n", a & b); // 00000001 -> 1

printf("a | b = %d\n", a | b); // 00000111 -> 7

printf("a ^ b = %d\n", a ^ b); // 00000110 -> 6

printf("~a = %d\n", ~a); // 11111010 -> 250 (unsigned)

printf("a << 1 = %d\n", a << 1); // 00001010 -> 10

printf("a >> 1 = %d\n", a >> 1); // 00000010 -> 2

return 0;

}

41. Unions¶

A union is a special data type that allows storing different data types in the same memory location. Only one member of the union can contain a value at any given time.

#include <stdio.h>

union Data {

int i;

float f;

char str[20];

};

int main() {

union Data data;

data.i = 10;

printf("data.i: %d\n", data.i);

data.f = 220.5;

// Accessing data.i now is incorrect as data.f was the last one set

printf("data.f: %f\n", data.f);

// The size of the union is the size of its largest member

printf("Size of union Data: %zu\n", sizeof(union Data));

return 0;

}

42. Enums-(Enumerations)¶

enum creates a user defined type consisting of a set of named integer constants. It improves code readability.

#include <stdio.h>

enum Weekday { MONDAY, TUESDAY, WEDNESDAY, THURSDAY, FRIDAY, SATURDAY, SUNDAY };

int main() {

enum Weekday today = WEDNESDAY;

// By default, enum constants start from 0

printf("Today is day number: %d\n", today); // Output: 2

if (today == WEDNESDAY) {

printf("It's hump day!\n");

}

return 0;

}

Part 6: Advanced and Specialized Topics¶

43. Multithreading with Pthreads¶

Concurrency in C is often achieved using the POSIX threads (Pthreads) library. This allows a program to perform multiple tasks simultaneously.

pthread_create(): Creates a new thread.pthread_join(): Waits for a thread to terminate.pthread_mutex_t: A mutex lock to protect shared data from race conditions.

Note: When compiling, you must link the pthread library with -pthread.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

void* thread_function(void* arg) {

printf("Hello from the new thread!\n");

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t thread_id;

// Create a new thread that will execute 'thread_function'

if (pthread_create(&thread_id, NULL, thread_function, NULL) != 0) {

perror("pthread_create failed");

return 1;

}

printf("Hello from the main thread!\n");

// Wait for the new thread to finish

if (pthread_join(thread_id, NULL) != 0) {

perror("pthread_join failed");

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

44. Atomics and Memory Barriers¶

For high performance concurrent code, C11 introduced atomic types and operations via <stdatomic.h>. These guarantee that operations are performed without interruption from other threads, often avoiding the need for heavier locks.

atomic_int: An integer type that can be manipulated atomically.atomic_fetch_add(): Atomically adds a value to an atomic object and returns the old value.- Memory Barriers (

atomic_thread_fence): Ensure that memory operations are ordered correctly across threads, preventing the compiler or CPU from reordering them in unsafe ways.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdatomic.h>

atomic_int counter = 0;

void* increment_counter(void* arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

// This operation is atomic and thread safe

atomic_fetch_add(&counter, 1);

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t t1, t2;

pthread_create(&t1, NULL, increment_counter, NULL);

pthread_create(&t2, NULL, increment_counter, NULL);

pthread_join(t1, NULL);

pthread_join(t2, NULL);

printf("Final counter value: %d\n", counter); // Should be 2,000,000

return 0;

}

45. Signal Handling¶

Signals are a form of inter process communication used in Unix like systems to notify a process of an event (e.g., SIGINT for Ctrl+C, SIGSEGV for a segmentation fault).

signal(): A basic way to set a signal handler.sigaction(): The recommended, more robust way to handle signals.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <unistd.h>

void handle_sigint(int sig) {

printf("\nCaught signal %d. Exiting gracefully.\n", sig);

exit(0);

}

int main() {

// Register handle_sigint as the handler for SIGINT

signal(SIGINT, handle_sigint);

printf("Running... Press Ctrl+C to exit.\n");

while (1) {

sleep(1);

}

return 0;

}

46. Inter-Process Communication-(IPC)¶

IPC allows different processes to communicate and synchronize. Common mechanisms include: - Pipes (pipe()): A unidirectional communication channel between related processes. - Shared Memory (shmget(), shmat()): A block of memory shared between multiple processes. This is the fastest form of IPC. - Message Queues (msgget(), msgsnd(), msgrcv()): A linked list of messages stored in the kernel.

47. Memory mapped Files-(mmap)¶

mmap() maps a file or device into memory. This allows file I/O to be treated as direct memory access, which can be much faster and simpler than using read() and write().

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

const char* text = "Hello, mmap!";

int fd = open("mmap_example.txt", O_RDWR | O_CREAT, (mode_t)0600);

// Set the file size

ftruncate(fd, strlen(text));

// Map the file into memory

char* map = mmap(0, strlen(text), PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

if (map == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("mmap failed");

close(fd);

return 1;

}

// Write to the file via the memory map

memcpy(map, text, strlen(text));

// Unmap the file and close the descriptor

munmap(map, strlen(text));

close(fd);

return 0;

}

48. Advanced Data Structures: Linked Lists¶

A linked list is a linear collection of data elements whose order is not given by their physical placement in memory. Each element points to the next.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

typedef struct Node {

int data;

struct Node* next;

} Node;

void print_list(Node* head) {

Node* current = head;

while (current != NULL) {

printf("%d -> ", current->data);

current = current->next;

}

printf("NULL\n");

}

int main() {

// Create a simple linked list: 1 -> 2 -> 3

Node* head = malloc(sizeof(Node));

head->data = 1;

head->next = malloc(sizeof(Node));

head->next->data = 2;

head->next->next = malloc(sizeof(Node));

head->next->next->data = 3;

head->next->next->next = NULL;

print_list(head);

// Remember to free the allocated memory

free(head->next->next);

free(head->next);

free(head);

return 0;

}

49. The volatile Keyword¶

The volatile keyword tells the compiler that a variable's value may change at any time without any action being taken by the code the compiler finds nearby. This prevents the compiler from applying optimizations that might assume the variable's value is constant.

It is used for: - Memory mapped hardware registers. - Variables shared between multiple threads (though atomics are often better). - Variables accessed by a signal handler.

// The compiler will not optimize away reads of this variable

volatile int sensor_value;

50. The const Keyword and its Nuances¶

const can be used with pointers in several ways, which can be confusing. Reading the declaration from right to left can help.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int val = 5;

int other_val = 10;

// `ptr_to_const` is a pointer to a constant integer.

// You cannot change the value it points to, but you can change the pointer.

const int* ptr_to_const = &val;

// *ptr_to_const = 7; // ILLEGAL

ptr_to_const = &other_val; // LEGAL

// `const_ptr` is a constant pointer to an integer.

// You can change the value it points to, but you cannot change the pointer.

int* const const_ptr = &val;

*const_ptr = 7; // LEGAL

// const_ptr = &other_val; // ILLEGAL

// `const_ptr_to_const` is a constant pointer to a constant integer.

// You can change neither the pointer nor the value it points to.

const int* const const_ptr_to_const = &val;

// *const_ptr_to_const = 7; // ILLEGAL

// const_ptr_to_const = &other_val; // ILLEGAL

return 0;

}

51. Generic Programming with _Generic¶

C11 introduced the _Generic keyword, which allows you to write macros that dispatch to different code based on the type of their argument.

#include <stdio.h>

#define-print_generic(x) _Generic((x), \

int: printf("Int: %d\n", x), \

float: printf("Float: %f\n", x), \

char*: printf("String: %s\n", x), \

default: printf("Other type\n") \

)

int main() {

print_generic(10);

print_generic(3.14f);

print_generic("Hello");

print_generic(1.0); // Will hit the default case (double)

return 0;

}

52. setjmp and longjmp: Non local Jumps¶

These functions provide a way to perform a "non local goto," jumping from one function to a setjmp call in another, without following the normal function call/return sequence. They are typically used for advanced error handling.

Warning: Use with extreme caution, as they can make code very difficult to understand and maintain.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <setjmp.h>

jmp_buf jump_buffer;

void risky_function() {

printf("In risky_function()... about to jump!\n");

longjmp(jump_buffer, 1); // Jump back to where setjmp was called

}

int main() {

// setjmp returns 0 on its first call.

// If longjmp is called, it will return the value passed to longjmp.

if (setjmp(jump_buffer) == 0) {

printf("setjmp has been initialized.\n");

risky_function();

} else {

printf("Jumped back into main!\n");

}

return 0;

}

53. Flexible Array Members¶

A flexible array member allows the last member of a struct to be a variable length array. This can be useful for creating contiguous data structures without a second memory allocation.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef struct {

int len;

char data[]; // Flexible array member must be the last member

} FlexString;

int main() {

int str_len = 10;

// Allocate memory for the struct AND the flexible array

FlexString* fs = malloc(sizeof(FlexString) + str_len + 1);

fs->len = str_len;

strcpy(fs->data, "0123456789");

printf("String: %s, Length: %d\n", fs->data, fs->len);

free(fs);

return 0;

}

54. The goto Statement¶

The goto statement provides an unconditional jump to a labeled statement within the same function. While often criticized, goto can be used responsibly to simplify complex error handling and cleanup logic in a function, avoiding deeply nested if statements.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int process_data() {

FILE* f = fopen("data.txt", "r");

if (!f) goto error_file;

void* mem = malloc(1024);

if (!mem) goto error_mem;

// ... process data ...

free(mem);

fclose(f);

return 0;

error_mem:

fclose(f);

error_file:

perror("An error occurred");

return -1;

}

55. Undefined Behavior, Sequence Points, and Strict Aliasing¶

Undefined Behavior (UB) means the C standard imposes no requirements on program behavior; compilers may assume it never happens and optimize accordingly.

Common UB examples: - Signed integer overflow (e.g., INT_MAX + 1) - Shifting by a negative amount or by >= width of the type - Accessing an object via an incompatible pointer type (strict aliasing) - Modifying a variable multiple times between sequence points (e.g., i = i++)

Strict aliasing and safe type punning:

#include <string.h>

float pun_int_to_float(int x) {

float f;

// Safe type punning via memcpy (avoids strict aliasing UB)

memcpy(&f, &x, sizeof f);

return f;

}

Mitigations and detection: - Prefer unsigned math for wraparound or check before operations - Use -fno strict aliasing if needed (better: avoid aliasing violations) - Enable UB sanitizers during testing: -fsanitize=undefined -fno omit frame pointer

56. Inline Functions and Linkage in Headers¶

When placing function definitions in headers, use static inline to avoid multiple definition errors at link time.

// util.h

#ifndef UTIL_H

#define UTIL_H

static inline int clampi(int v, int lo, int hi) {

return v < lo ? lo : (v > hi ? hi : v);

}

#endif // UTIL_H

Notes: - static grants internal linkage per translation unit - extern inline has subtle differences across standards; prefer static inline in headers

57. Endianness and Byte Order¶

Endianness defines how multi byte values are stored. Use standardized conversions for network protocols.

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

uint32_t host = 0x11223344u;

uint32_t net = htonl(host); // host -> network (big endian)

printf("host=0x%08x net=0x%08x\n", host, net);

return 0;

}

To detect at runtime:

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

uint32_t x = 1; unsigned char b[4];

memcpy(b, &x, 4);

if (b[0] == 1) puts("little endian"); else puts("big endian");

return 0;

}

58. POSIX Low level I/O¶

Use open/read/write/close for fine grained control. Always handle partial reads/writes and EINTR.

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

ssize_t write_all(int fd, const void *buf, size_t len) {

const char *p = buf; size_t n = len;

while (n > 0) {

ssize_t w = write(fd, p, n);

if (w < 0) {

if (errno == EINTR) continue;

return -1;

}

p += (size_t)w; n -= (size_t)w;

}

return (ssize_t)len;

}

Open with CLOEXEC to avoid fd leaks across exec:

int fd = open("out.bin", O_WRONLY|O_CREAT|O_TRUNC|O_CLOEXEC, 0644);

59. errno and Error Handling¶

errno is thread local and set by failing library/system calls. Read it immediately after failure.

#include <errno.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void demo(FILE *f) {

if (fclose(f) != 0) {

int e = errno; // capture early

fprintf(stderr, "fclose failed: %s\n", strerror(e));

}

}

Prefer perror("context") for quick diagnostics. Use strerror_r where available for thread safe messages.

60. Randomness and Secure RNG¶

Do not use rand() for security. Better options: - Linux: getrandom(2) via

#if-defined(__linux__)

#include <sys/random.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){ unsigned int x; if (getrandom(&x, sizeof x, 0) != sizeof x) return 1; printf("%u\n", x); }

#else

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){ unsigned int x; int fd=open("/dev/urandom",O_RDONLY); if(fd<0) return 1; ssize_t r=read(fd,&x,sizeof x); close(fd); if(r!=sizeof x) return 1; printf("%u\n", x);}

#endif

61. Floating Point Pitfalls and IEEE-754¶

Avoid direct equality comparisons; use an epsilon. Handle NaN/Inf explicitly.

#include <math.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

bool fequal(double a, double b, double eps) {

return fabs(a b) <= eps * fmax(1.0, fmax(fabs(a), fabs(b)));

}

Use isnan, isfinite, and fenv for rounding modes and exceptions when needed.

62. Build Systems: Minimal Makefile¶

A tiny makefile that builds all .c in src/ into bin/app:

CC=gcc

CFLAGS=-std=c11 -Wall -Wextra -O2 -g

LDFLAGS=

SRC=$(wildcard src/*.c)

OBJ=$(SRC:src/%.c=build/%.o)

BIN=bin/app

$(BIN): $(OBJ)

@mkdir -p $(dir $@)

$(CC) $(OBJ) -o $@ $(LDFLAGS)

build/%.o: src/%.c

@mkdir -p $(dir $@)

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c $< -o $@

clean:

rm -rf build $(BIN)

Part 7: Security-Focused C Cookbook¶

63. Secure CLI Parsing with getopt/getopt_long¶

Use getopt/getopt_long to parse options safely. Avoid manual argv parsing.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <getopt.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

const char *file = NULL; int verbose = 0;

static struct option longopts[] = {

{"file", required_argument, 0, 'f'},

{"verbose", no_argument, 0, 'v'},

{"help", no_argument, 0, 'h'},

{0,0,0,0}

};

int c;

while ((c = getopt_long(argc, argv, "f:vh", longopts, NULL)) != -1) {

switch (c) {

case 'f': file = optarg; break;

case 'v': verbose++; break;

case 'h': printf("Usage: %s [-v] -f <file>\n", argv[0]); return 0;

default: return 1;

}

}

if (!file) { fprintf(stderr, "-f <file> is required\n"); return 1; }

if (verbose) fprintf(stderr, "Processing %s\n", file);

// ...

return 0;

}

64. Safe String Handling Patterns¶

- Use snprintf for formatting; check truncation via return value

- Prefer strnlen over strlen on untrusted input

- Parse integers with strtol/strtoul and validate errors

- Use strtok_r for re entrant tokenization

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <errno.h>

long parse_long(const char *s) {

errno = 0; char *end; long v = strtol(s, &end, 10);

if (errno || end == s || *end != '\0') { fprintf(stderr, "bad int: %s\n", s); exit(1);}

return v;

}

void join_two(const char *a, const char *b, char *out, size_t outsz){

int n = snprintf(out, outsz, "%s_%s", a, b);

if (n < 0 || (size_t)n >= outsz) { fprintf(stderr, "truncated\n"); }

}

65. Secure Temporary Files with mkstemp¶

Avoid tmpnam/mkstemp patterns that return names only. Use mkstemp and write to the returned fd.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

int main(void){

char tmpl[] = "/tmp/myappXXXXXX"; // must be writable buffer

int fd = mkstemp(tmpl);

if (fd == -1) { perror("mkstemp"); return 1; }

// tmpl now holds the unique filename; fd is open O_EXCL

dprintf(fd, "hello\n");

// Optionally unlink for anonymity (deleted on close if no other links)

// unlink(tmpl);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

66. Privilege Dropping and Chroot¶

If running as root temporarily, drop privileges early and permanently.

#include <unistd.h>

#include <grp.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void drop_privileges(uid_t uid, gid_t gid) {

if (setgroups(0, NULL) != 0) { perror("setgroups"); exit(1);} // clear supplementary groups

if (setgid(gid) != 0) { perror("setgid"); exit(1);}

if (setuid(uid) != 0) { perror("setuid"); exit(1);}

if (setuid(0) != -1) { fprintf(stderr, "Privilege drop failed\n"); exit(1);} // ensure not regainable

}

int main(void){

if (geteuid() == 0) {

// Optionally chroot to a safe directory first

// if (chroot("/var/empty") || chdir("/")) { perror("chroot"); exit(1);}

drop_privileges(1000, 1000); // example: to UID/GID 1000

}

// ... run unprivileged ...

return 0;

}

Note: On Linux consider capabilities instead of full root; e.g., CAP_NET_BIND_SERVICE for low ports.

67. Constant time Comparisons¶

Avoid timing leaks in secret comparisons.

#include <stddef.h>

int ct_memcmp(const unsigned char *a, const unsigned char *b, size_t n){

unsigned char diff = 0;

for (size_t i=0; i<n; i++) diff |= (unsigned char)(a[i] ^ b[i]);

return diff; // 0 if equal

}

68. Password Hashing and Key Derivation¶

Prefer modern KDFs. Examples: - libsodium: crypto_pwhash_argon2id - OpenSSL: PKCS5_PBKDF2_HMAC

libsodium (recommended):

// gcc main.c -lsodium

#include <sodium.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){

if (sodium_init() < 0) return 1;

const char *pwd = "secret"; unsigned char salt[crypto_pwhash_SALTBYTES];

randombytes_buf(salt, sizeof salt);

unsigned char key[32];

if (crypto_pwhash(key, sizeof key, pwd, strlen(pwd), salt,

crypto_pwhash_OPSLIMIT_INTERACTIVE, crypto_pwhash_MEMLIMIT_INTERACTIVE,

crypto_pwhash_ALG_DEFAULT) != 0) return 1;

printf("key[0]=%u\n", key[0]);

return 0;

}

OpenSSL PBKDF2:

// gcc main.c -lcrypto

#include <openssl/evp.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(void){

const char *pwd = "secret"; const unsigned char salt[] = {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8};

unsigned char key[32];

if (!PKCS5_PBKDF2_HMAC(pwd, (int)strlen(pwd), salt, (int)sizeof salt, 100000,

EVP_sha256(), (int)sizeof key, key)) return 1;

printf("key[0]=%u\n", key[0]);

return 0;

}

69. Logging with syslog¶

#include <syslog.h>

int main(void){

openlog("myapp", LOG_PID|LOG_CONS, LOG_USER);

syslog(LOG_INFO, "Starting up");

syslog(LOG_ERR, "An error occurred: %d", 42);

closelog();

return 0;

}

70. File Permissions and umask¶

Ensure correct file modes when creating files.

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(void){

mode_t old = umask(077); // default to 600 for created files

int fd = open("secret.txt", O_WRONLY|O_CREAT|O_TRUNC, 0600);

umask(old);

if (fd < 0) return 1;

write(fd, "top secret\n", 11);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

71. Monotonic Time and Timeouts¶

Use CLOCK_MONOTONIC for measuring intervals.

#include <time.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){

struct timespec a,b; clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &a);

// ... work ...

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &b);

double ms = (b.tv_sec a.tv_sec)*1000.0 + (b.tv_nsec a.tv_nsec)/1e6;

printf("elapsed: %.3f ms\n", ms);

return 0;

}

Part 8: Networking and Systems Cookbook¶

72. TCP Client¶

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){

int s = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

struct sockaddr_in addr = { .sin_family = AF_INET, .sin_port = htons(80) };

inet_pton(AF_INET, "93.184.216.34", &addr.sin_addr); // example.com

if (connect(s, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, sizeof addr) != 0) return 1;

const char *req = "GET / HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: example.com\r\n\r\n";

send(s, req, strlen(req), 0);

char buf[1024]; ssize_t n;

while ((n = recv(s, buf, sizeof buf, 0)) > 0) write(1, buf, (size_t)n);

close(s); return 0;

}

73. TCP Server¶

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

int main(void){

int s = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

int on = 1; setsockopt(s, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEADDR, &on, sizeof on);

struct sockaddr_in addr = { .sin_family=AF_INET, .sin_port=htons(8080), .sin_addr={htonl(INADDR_ANY)} };

bind(s, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, sizeof addr);

listen(s, 16);

for (;;) {

int c = accept(s, NULL, NULL);

const char *msg = "Hello from server!\n";

send(c, msg, strlen(msg), 0);

close(c);

}

}

74. UDP Echo¶

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(void){

int s = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_DGRAM, 0);

struct sockaddr_in addr = { .sin_family=AF_INET, .sin_port=htons(9999), .sin_addr={htonl(INADDR_ANY)} };

bind(s, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, sizeof addr);

for (;;) {

char buf[1500]; struct sockaddr_in cli; socklen_t len = sizeof cli;

ssize_t n = recvfrom(s, buf, sizeof buf, 0, (struct sockaddr*)&cli, &len);

sendto(s, buf, (size_t)n, 0, (struct sockaddr*)&cli, len);

}

}

75. UNIX Domain Sockets¶

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/un.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){

const char *path = "/tmp/unix.sock";

int s = socket(AF_UNIX, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

struct sockaddr_un addr = { .sun_family = AF_UNIX }; strncpy(addr.sun_path, path, sizeof addr.sun_path 1);

unlink(path); bind(s, (struct sockaddr*)&addr, sizeof addr); listen(s, 5);

int c = accept(s, NULL, NULL); write(c, "hi\n", 3); close(c); close(s); unlink(path);

return 0;

}

76. select based Multiplexing¶

#include <sys/select.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){

fd_set rfds; FD_ZERO(&rfds); FD_SET(0, &rfds); // stdin

struct timeval tv = { .tv_sec = 2, .tv_usec = 0 };

int r = select(1, &rfds, NULL, NULL, &tv);

if (r > 0 && FD_ISSET(0, &rfds)) puts("stdin ready");

else if (r == 0) puts("timeout");

return 0;

}

77. Packet Capture with libpcap¶

// gcc snif.c $(pkg config --cflags --libs libpcap)

#include <pcap/pcap.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void cb(u_char *user, const struct pcap_pkthdr *h, const u_char *bytes){

printf("pkt len=%u first=%02x\n", h->len, bytes[0]);

}

int main(){

char err[PCAP_ERRBUF_SIZE];

pcap_t *p = pcap_open_live("any", 65535, 1, 1000, err);

if (!p) { fprintf(stderr, "%s\n", err); return 1; }

pcap_loop(p, 5, cb, NULL);

pcap_close(p); return 0;

}

78. TLS Notes with OpenSSL¶

- Use the high level EVP and SSL APIs; validate certificates!

- Minimal client skeleton:

// Link: pkg config --cflags --libs openssl #include <openssl/ssl.h> #include <openssl/err.h> int main(){ SSL_library_init(); SSL_load_error_strings(); const SSL_METHOD *m = TLS_client_method(); SSL_CTX *ctx = SSL_CTX_new(m); SSL_CTX_set_default_verify_paths(ctx); // Create TCP socket and connect()... // SSL *ssl = SSL_new(ctx); SSL_set_fd(ssl, sock); SSL_set_tlsext_host_name(ssl, "example.com"); // if (SSL_connect(ssl) != 1) ERR_print_errors_fp(stderr); // SSL_get_verify_result(ssl) == X509_V_OK ? ... : ... // Cleanup: SSL_free(ssl); SSL_CTX_free(ctx); return 0; }

79. Serialization and TLV¶

Structure messages with explicit lengths and network byte order.

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

typedef struct { uint16_t type; uint16_t len; unsigned char data[256]; } TLV;

size_t tlv_pack(uint16_t t, const void *buf, uint16_t len, unsigned char *out){

TLV m; m.type = htons(t); m.len = htons(len); memcpy(m.data, buf, len);

memcpy(out, &m, 4u + len); return 4u + len;

}

Part 9: Project Structure and Build¶

80. Project Skeleton¶

A simple, portable layout:

myapp/

src/ # .c sources

include/ # public headers

tests/ # unit tests

Makefile

Build tips: - Use -Wall -Wextra -Werror in CI; relax locally if needed - Keep headers self contained and include guarded

81. Unit Testing with CMocka¶

// gcc test.c -o test -lcmocka

#include <stdarg.h>

#include <stddef.h>

#include <setjmp.h>

#include <cmocka.h>

static void test_add(void **state) {

(void)state; assert_int_equal(2+2, 4);

}

int main(void){

const struct CMUnitTest tests[] = { cmocka_unit_test(test_add) };

return cmocka_run_group_tests(tests, NULL, NULL);

}

82. Cross compilation and Static Builds¶

- Static glibc: gcc -static -O2 -s main.c -o app.static

- musl (recommended for smaller static builds): x86_64-linux musl gcc main.c -o app

- Windows (MinGW): x86_64-w64-mingw32-gcc main.c -lws2_32 -o app.exe

83. Continuous Integration (GitHub-Actions)¶

name: C CI

on: [push, pull_request]

jobs:

build:

runs on: ubuntu latest

steps:

uses: actions/checkout@v4

run: sudo apt get update && sudo apt get install -y build essential cmocka doc cmocka dev

run: make -j$(nproc)

run: gcc tests/test.c -o test -lcmocka && ./test

Part 10: Crypto and Security Primitives¶

84. AES-GCM with OpenSSL EVP¶

Authenticated encryption example (errors elided for brevity):

// gcc gcm.c -lcrypto

#include <openssl/evp.h>

#include <string.h>

int aes_gcm_encrypt(const unsigned char *key, const unsigned char *iv,

const unsigned char *aad, int aad_len, const unsigned char *pt, int pt_len,

unsigned char *ct, unsigned char tag[16])

{

EVP_CIPHER_CTX *ctx = EVP_CIPHER_CTX_new();

int len, outlen = 0;

EVP_EncryptInit_ex(ctx, EVP_aes_256_gcm(), NULL, NULL, NULL);

EVP_CIPHER_CTX_ctrl(ctx, EVP_CTRL_GCM_SET_IVLEN, 12, NULL);

EVP_EncryptInit_ex(ctx, NULL, NULL, key, iv);

if (aad && aad_len) EVP_EncryptUpdate(ctx, NULL, &len, aad, aad_len);

EVP_EncryptUpdate(ctx, ct, &len, pt, pt_len); outlen += len;

EVP_EncryptFinal_ex(ctx, ct+outlen, &len); outlen += len;

EVP_CIPHER_CTX_ctrl(ctx, EVP_CTRL_GCM_GET_TAG, 16, tag);

EVP_CIPHER_CTX_free(ctx);

return outlen;

}

85. HMAC and Hashing¶

// gcc hmac.c -lcrypto

#include <openssl/hmac.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){

const unsigned char key[] = "k"; const unsigned char msg[] = "data";

unsigned char mac[EVP_MAX_MD_SIZE]; unsigned int maclen=0;

HMAC(EVP_sha256(), key, (int)strlen((char*)key), msg, strlen((char*)msg), mac, &maclen);

printf("maclen=%u\n", maclen); return 0;

}

86. Ed25519 Sign/Verify-(libsodium)¶

// gcc ed.c -lsodium

#include <sodium.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void){

if (sodium_init()<0) return 1;

unsigned char pk[crypto_sign_PUBLICKEYBYTES], sk[crypto_sign_SECRETKEYBYTES];

crypto_sign_keypair(pk, sk);

unsigned char msg[] = "hi", sig[crypto_sign_BYTES];

crypto_sign_detached(sig, NULL, msg, sizeof msg-1, sk);

printf("ok? %d\n", crypto_sign_verify_detached(sig, msg, sizeof msg-1, pk)==0);

return 0;

}

87. Secrets Management Guidelines¶

- Never hardcode secrets; load from environment or dedicated secret store

- Zero sensitive buffers after use (explicit_bzero/OPENSSL_cleanse)

- Limit secret lifetime and process privileges; prefer separate processes